Read the rest of this article...

Friday, May 19, 2023

A Centuries-Old Mystery: Did This Elusive Viking City Exist?

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, May 08, 2023

Viking Burial Goods: 10 Exotic Items the Vikings Took to Valhalla

Read the rest of this article...

Is There Something Fishy About Radiocarbon Dating?

Hel-hama, own work, via Wikipedia

Read the rest of this article...

Thursday, May 04, 2023

Seemingly 'empty' burial mound is hiding a 1,200-year-old Viking ship

(Image credit: Theo B. Gill – The Museum of Archaeology, University of Stavanger)

20-METRE-LONG VIKING SHIP FOUND IN NORWAY

Read the rest of this article...

Rare, 1,000-year-old Viking Age iron hoard found in basement in Norway

Read the rest of this article...

How Accurate Are the Viking Sagas?

Read the rest of this article...

How Were Viking Ships Built and Buried?

Read the rest of this article...

Tuesday, May 02, 2023

New Genetic Study of Scotland’s Picts

A new genetic study has offered insight into the geographic origins and social organization of the Picts of Scotland, according to a report from Live Science. The Picts’ name is derived from the Latin word picti and references their use of body paint or tattoos. In the third century A.D., they fought off the Romans and established a kingdom in northern Britain that survived until around A.D. 900. Little is known of the Picts, but early medieval historians suggested they came from the Aegean Sea or Eastern Europe and that they traced their descent through their mother’s side. The new study, led by Adeline Morez of Liverpool John Moores University and Linus Girdland-Flink of the University of Aberdeen, analyzed genetic material from eight skeletons—seven from the Lundin Links cemetery and one from the Balintore cemetery, both in present-day Scotland.

Read the rest of this article...

DNA study sheds light on Scotland’s Picts, and resolves some myths about them

The people known as the Picts have puzzled archaeologists and historians for centuries. They lived in Scotland during the early medieval period, from around AD300 to AD900, but many aspects of their society remain mysterious.

The Picts’ unique cultural characteristics, such as large stones decorated with distinct symbols, and lack of written records, have led to numerous theories about their origins, way of life, and culture.

This is commonly referred to in archaeology as the “Pictish problem”, a term popularised by the title of a 1955 edited book by the archaeologist Frederick Threlfall Wainwright.

Read the rest of this article...The Shadowy Kingdom Of Gewissae, Britain’s First Kings

Read the rest of this article...

Tiny Bead, Found In Bulgaria, Is World's Oldest Gold

Read the rest of this article...

Researchers discover what triggered Earth's last ice age

At the beginning of the last ice, local mountain glaciers grew and formed large ice sheets, like the one seen here. (CREDIT: Creative Commons)

For quite some time, paleo-climate specialists have been perplexed by two enigmas: What was the origin of the ice sheets that defined the final ice age, and how could they expand so rapidly?

A fresh research conducted by the University of Arizona's experts suggests a plausible explanation for the swift expansion of the ice sheets that coated a considerable portion of the Northern Hemisphere during the last ice age. Furthermore, the study's findings may be applicable to other glacial periods in the Earth's past.

Read the rest of this article...

The puzzle of Neanderthal aesthetics

Read the rest of this article...

Video – Viking Age fortresses on the North Frisian islands

Read the rest of this article...

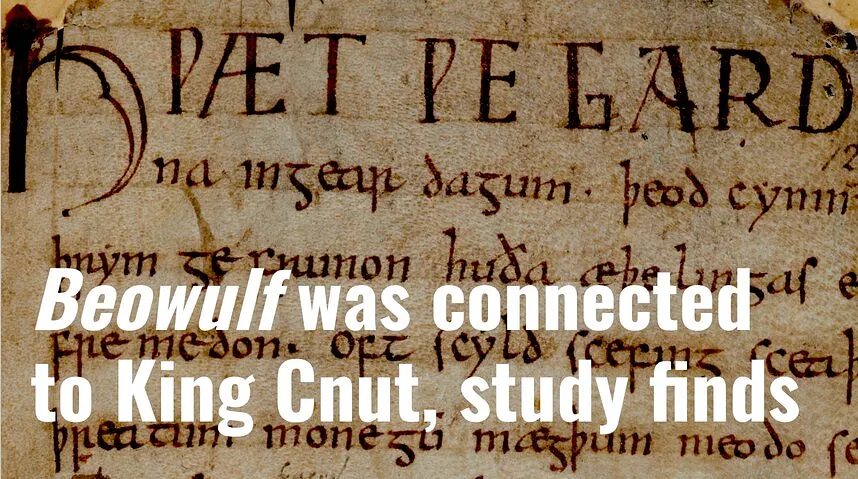

Beowulf was connected to King Cnut, study finds

Read the rest of this article...

Stolen coins reveals King Alfred had help from ally to stop Vikings ruling England

Read the rest of this article...

Double hoard of Viking treasure discovered near Harald Bluetooth's fort in Denmark

Read the rest of this article...