Wednesday, August 12, 2020

About 30 previously unknown stones discovered at Carahunge (the Armenian Stonehenge)

About 30 previously unknown stones with holes have been discovered at Carahunge or Zorats Karer (the Armenian Stonehenge).

Other stones of astronomical importance have also been found during the measurement works carried out jointly by the Byurakan Observatory and the Armenian National University of Architecture and Construction.

The team carried out computer scanning of the monument and the adjacent area, aerial photo-scanning of the area. All stones with holes were photographed and measured.

Read the rest of this article...

DES TOMBES GAULOISES AUX PORTES DE NÎMES (GARD)

À l'ouest du centre-ville de Nîmes, l'Inrap vient de mettre à jours des vestiges de l’âge du Fer à l’Antiquité ; sépultures, champs et voirie.

Sur prescription de la DRAC Occitanie, une fouille préventive menée par l’Inrap s’est déroulée de mai à août 2020, à l’ouest du centre-ville actuel de la ville de Nîmes, préalablement à la construction d’un immeuble d’habitation.

DES TOMBES GAULOISES

La découverte principale de cette opération est un ensemble funéraire en bon état de conservation dont l’emprise s’étend au-delà des limites de la fouille. Daté entre les VIe et Ve siècles avant notre ère, cet ensemble comprend trois sépultures à incinération, deux vases ossuaires en céramique grise monochrome et un dépôt de résidus en fosse. Le mobilier métallique associé, couteaux et fibules, indique qu’il s’agit pour deux d’entre elles de personnages appartenant à la sphère masculine.

Read the rest of this article...

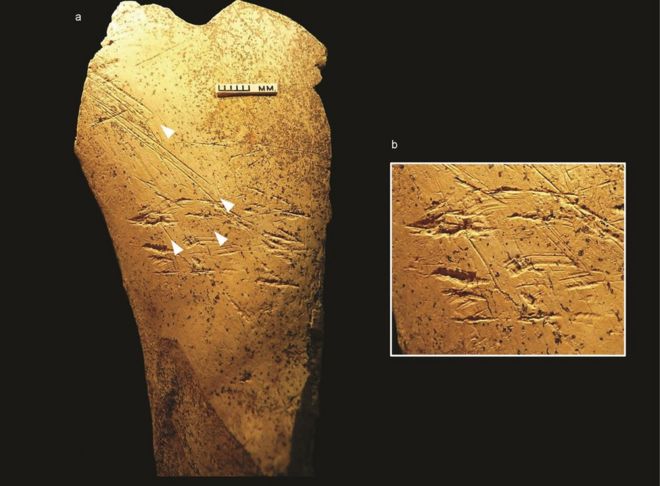

Europe's earliest bone tools found in Britain

One of the oldest organic tools in the world. A bone hammer used to make the fine flint bifaces from Boxgrove. The bone shows scraping marks used to prepare the bone as well as pitting left behind from its use in making flint tools

UCL INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY

The implements come from the renowned Boxgrove site in West Sussex, which was excavated in the 1980s and 90s.

The bone tools came from a horse that humans butchered at the site for its meat.

Flakes of stone in piles around the animal suggest at least eight individuals were making large flint knives for the job.

Researchers also found evidence that other people were present nearby - perhaps younger or older members of a community - shedding light on the social structure of our ancient relatives.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, August 10, 2020

"Woodhenge” discovered in prehistoric complex of Perdigões

Archaeological excavations in the Perdigões complex, in the Évora district, have identified "a unique structure in the Prehistory of the Iberian Peninsula", Era -Arqueologia announced.

Speaking to the Lusa agency, the archaeologist in charge, António Valera, said that it was "a monumental wooden construction, of which the foundations remain, with a circular plan and more than 20 metres in diameter".

It is "a ceremonial construction", a type of structure only known in Central Europe and the British Isles, according to the archaeologist, with the designations as 'Woodhenge', "wooden versions of Stonehenge", or 'Timber Circles' (wooden circles).

The structure now identified is located in the centre of the large complex of ditch enclosures in Perdigões and "articulates with the visibility of the megalithic landscape that extends between the site and the elevation of Monsaraz, located to the east, on the horizon".

Read the rest of this article...

Yarm Viking helmet 'first' to be unearthed in Britain

The Viking helmet was essential personal protective equipment for a warrior

DURHAM UNIVERSITY

A Viking helmet unearthed in Yarm in the 1950s is the first to ever be found in Britain, according to new research.

Found in Chapel Yard by workmen digging trenches for new sewerage pipes, the corroded, damaged artefact is a rare, 10th century Anglo-Scandinavian helmet.

A research project led by Dr Chris Caple also found it is only the second near-complete Viking helmet found in the world.

It has been on display at Preston Park Museum since 2012.

The age of the helmet had caused much debate until now.

Researchers used evidence from recent archaeological discoveries as well as analysis of the metal and corrosion to reveal its past

Read the rest of this article...

A new analysis of 1st Temple-era artifacts, magnetized when Babylonians torched the city, provides a way to chart the geomagnetic field – physics’ Holy Grail – and maybe save Earth The Bible and pure science converge in a new archaeomagnetism study of a large public structure that was razed to the ground on Tisha B’Av 586 BCE during the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. The resulting data significantly boosts geophysicists’ ability to understand the “Holy Grail” of Earth sciences — Earth’s ever-changing magnetic field. “The magnetic field is invisible, but it plays a critical role in the life of our planet. Without the geomagnetic field, nothing on Earth would be as it is — maybe life wouldn’t have evolved without it,” Hebrew University Prof. Ron Shaar, a co-author of the study, told The Times of Israel. In the new study published in the PLOS One scientific journal, lead author and archaeologist Yoav Vaknin harvested data from pieces of floor from a large, two-story building excavated in the City of David’s Givati parking lot. Minerals embedded in the dozens of floor chunks were heated at a temperature higher than 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius) and magnetized during the slash and burning of ancient Jerusalem, and therefore offered up geomagnetic coordinates. Read the rest of this article...

An iron helmet that was discovered in Yarm, North Yorkshire, during sewer work in the 1950s has been confirmed to be an extremely rare Viking-era helmet, only the second nearly complete Viking helmet in the world and the first and only one found in Britain.

It was referred to as the Viking helmet from the beginning, but its real age has been an open discussion since its find. It has design elements found in earlier forms from the Anglo-Saxon and Vendel era, and because the only other helmet in the world confirmed to date to the Viking era, the Gjermundbu Helmet found in Haugsbygd, Norway, in 1943, was not a direct comparison, it was difficult to conclusively identify the Yarm Helmet as an Anglo-Scandinavian piece. A new study by Durham University researchers has used recent archaeological finds and analysis of the iron and corrosion products to narrow down its age of manufacture. It is indeed an Anglo-Scandinavian helmet made in northern England in the 10th century.

Read the rest of this article...

Burnt remains from 586 BCE Jerusalem may hold key to protecting planet

A new analysis of 1st Temple-era artifacts, magnetized when Babylonians torched the city, provides a way to chart the geomagnetic field – physics’ Holy Grail – and maybe save Earth

The Bible and pure science converge in a new archaeomagnetism study of a large public structure that was razed to the ground on Tisha B’Av 586 BCE during the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. The resulting data significantly boosts geophysicists’ ability to understand the “Holy Grail” of Earth sciences — Earth’s ever-changing magnetic field.

“The magnetic field is invisible, but it plays a critical role in the life of our planet. Without the geomagnetic field, nothing on Earth would be as it is — maybe life wouldn’t have evolved without it,” Hebrew University Prof. Ron Shaar, a co-author of the study, told The Times of Israel.

In the new study published in the PLOS One scientific journal, lead author and archaeologist Yoav Vaknin harvested data from pieces of floor from a large, two-story building excavated in the City of David’s Givati parking lot. Minerals embedded in the dozens of floor chunks were heated at a temperature higher than 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius) and magnetized during the slash and burning of ancient Jerusalem, and therefore offered up geomagnetic coordinates.

Read the rest of this article...

Detectorist 'shaking with happiness' after Bronze Age find

Items believed to be pieces of the Bronze Age harness were also found

CROWN COPYRIGHT

A metal detectorist was left "shaking with happiness" after discovering a hoard of Bronze Age artefacts in the Scottish Borders.

A complete horse harness and sword was uncovered by Mariusz Stepien at the site near Peebles in June.

Experts said the discovery was of "national significance".

The soil had preserved the leather and wood, allowing experts to trace the straps that connected the rings and buckles.

This allowed the experts to see for the first time how Bronze Age horse harnesses were assembled.

Mr Stepien was searching the field with friends when he found a bronze object buried half a metre underground.

He said: "I thought 'I've never seen anything like this before' and felt from the very beginning that this might be something spectacular and I've just discovered a big part of Scottish history.

Read the rest of this article...

Metal detectorist unearths ‘nationally significant’ Bronze Age hoard

Bronze Age harness

A metal detectorist has discovered a hoard of Bronze Age artefacts in the Scottish Borders which experts have described as “nationally significant”.

Mariusz Stepien, 44, was searching a field near Peebles with friends on June 21 when he found a bronze object buried half a metre underground.

The group camped in the field and built a shelter to protect the find from the elements while archaeologists spent 22 days investigating.

Among the items found were a complete horse harness – preserved by the soil – and a sword which have been dated as being from 1000 to 900 BC.

Mr Stepien said: “I thought I’ve never seen anything like this before and felt from the very beginning that this might be something spectacular and I’ve just discovered a big part of Scottish history.

Read the rest of this article...

Mystery ancestor mated with ancient humans. And its 'nested' DNA was just found.

An unidentified ancestor that interbred with humans may have been Homo erectus (skull shown here).

(Image: © Shutterstock)

The ancestor may have been Homo erectus, but no one knows for sure — the genome of that extinct species of human has never been sequenced, said Adam Siepel, a computational biologist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and one of the authors of a new paper examining the relationships of ancient human ancestors.

The new research, published today (Aug. 6) in the journal PLOS Genetics, also finds that ancient humans mated with Neanderthals between 200,000 and 300,000 years ago, well before the more recent, and better-known mixing of the two species occurred, after Homo sapiens migrated in large numbers out of Africa and into Europe 50,000 years ago. Thanks to this ancient mixing event, Neanderthals actually owe between 3% and 7% of their genomes to ancient Homo sapiens, the researchers reported.

Read the rest of this article...

Wednesday, August 05, 2020

Lost Viking waterway found in Orkney

The lost Viking waterway likely connected farms on Orkney Mainland to the power bases of the Norse earls on the north west coast at Birsay. PIC: St Andrews University.

Now it is believed that Vikings were using a route from Harray in the central mainland through the Loch of Banks to a portage at Twatt before reaching the Loch of Boardhouse and ultimately the coastal powerbases of the Norse Earls at the Brough of Birsay, a tidal island off the very tip of the north west coast.

The waterway network would have provided a shallow route through which the Vikings were able to haul both their boats and heavy goods, such as grain.

Taxes and rents may have been gathered from the farms around Harray and transported on the waterway to Birsay with the route also offering a way to the waters of Scapa Flow and the North Atlantic.

Read the rest of this article...

Richard the Lionheart’s absent Queen of England is returned to her rightful place

The tomb effigy of Berengaria of Navarre has been exposed to the elements over the past 50 years

The tomb effigy of Richard the Lionheart’s wife, Berengaria of Navarre, was sculpted upon her death in 1230 as a sign of respect. Yet over the past couple of centuries, there seems to have been scant regard in France for the only English queen who is never thought to have set foot in England.

Since the French Revolution in 1789, Berengaria’s effigy has been broken, moved several times, left in a barn, lost and found again covered in wheat and hay. Its latest resting place is the chapterhouse at Epau abbey in central France, where it is exposed to the elements.

Read the rest of this article...

Ancient Viking waterway discovered in Orkney

A lost Viking canal system that acted as a trade and transport highway, has been discovered running through Orkney.

The route connects the North Atlantic with the Scapa Flow and crosses the Scottish archipelago’s mainland.

A series of Old Norse place names around the island, connected to the sea and boats, first sparked the interest of researchers who then began investigations.

Modern scientific methods, geophysical mapping and sediment samples have now revealed that the area was connected through a series of ancient canals.

Read the rest of this article...

Skeletons reveal wealth gap in Europe began to open 6600 years ago

Some early European farmers seem to have been much better off than others

Chelsea Budd/Umeå University

A wealth gap may have existed far earlier than we thought, providing insight into the lives of some of Europe’s earliest farmers.

Chelsea Budd at Umeå University in Sweden and her colleagues analysed the 6600-year-old grave sites of the Osłonki community in Poland, to try to determine whether wealth inequality existed in these ancient societies.

The team first found that a quarter of the population was buried with expensive copper beads, pendants and headbands. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that these people were richer during their lifetimes.

“The items could simply have been a performance by the surviving family members,” says Budd. “It could be used to mitigate the processes surrounding death or even to promote their own social status.”

Read the rest of this article...

Remains of 10,000-year-old woolly mammoth pulled from Siberian lake

A newly discovered woolly mammoth skeleton found on the Yamal peninsula in Siberia, Russia, is remarkably well preserved. Photograph: mvk.yanao/ Instagram

Rare find includes skin, tendon and excrement of what is thought to be an adult male

Russian scientists are poring over the uniquely well-preserved bones of a 10,000-year-old woolly mammoth after completing the operation to pull them from the bottom of a Siberian lake.

Experts spent five days scouring the silt of Lake Pechenelava-To in the remote Yamal peninsula for the remains, which include tendons, skin and even excrement, after they were spotted by local residents. About 90% of the animal has been retrieved during two expeditions.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, August 03, 2020

Update on the Asclepeion dig at Epidaurus

Credit: Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports

Culture Minister Lina Mendoni on Thursday visited the archaeological site at the Epidaurus Asclepeion to be briefed on the progress of recent archaeological excavations which have revealed the remains of an even older temple building found at the shrine, in the vicinity of the Tholos.

The partially-excavated building, which is dated to about 600 B.C., consists of a ground floor with a primitive colonnade and an underground basement chipped out of the rock beneath. The stone walls of the basement are covered in a deep-red-colored plaster and the floor is an intact pebble mosaic, which is one of the best-preserved examples of this rare type of flooring to survive from this era.

The find is considered significant because it predates the impressive Tholos building in the same location, whose own basement served as the chthonic residence of Asclepius, and which replaced the newly-discovered structure after the 4th century B.C.

Read the rest of this article...

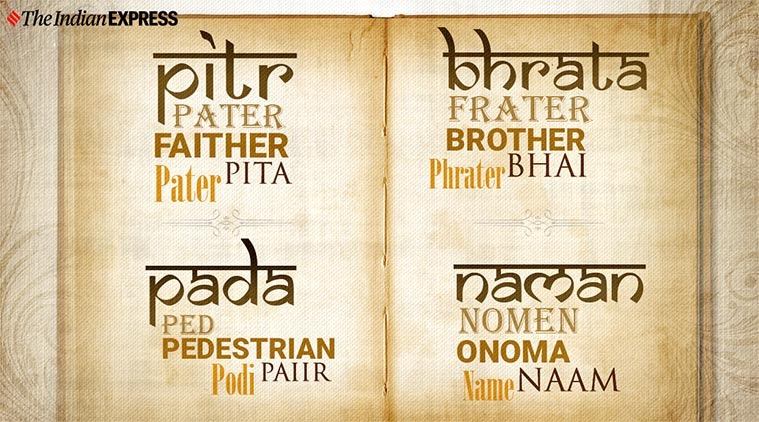

Why Sanskrit has strong links to European languages and what it learnt in India

Jones’ claim rested on the evidence of several Sanskrit words that had similarities with Greek and Latin. (Photo created by Gargi Singh)

Newer scholarship has shown that even though Sanskrit did indeed share a common ancestral homeland with European and Iranian languages, it had also borrowed quite a bit from pre-existing Indian languages in India.

In 1783, the colonial stage in Bengal saw the entrance of William Jones who was appointed judge of the Supreme Court of Judicature at Fort William. In the next couple of years, Jones established himself as an authority on ancient Indian language and culture, a field of study that was hitherto untouched. His obsession with the linguistic past of the subcontinent, led him to propose that there existed an intimate relationship between Sanskrit and languages spoken in Europe.

Jones’ claim rested on the evidence of several Sanskrit words that had similarities with Greek and Latin. For instance, the Sanskrit word for ‘three’, that is ‘trayas’, is similar to the Latin ‘tres’ and the Greek ‘treis’. Similarly, the Sanskrit for ‘snake’, is ‘sarpa’, which shares a phonetic link with ‘serpens’ in Latin. As he studied the languages further, it became clearer that apart from Greek and Latin, Sanskrit words could be found in most other European languages.

Read the rest of this article...

Sunday, August 02, 2020

Ancient bones in disturbed peat bogs are rotting away, alarming archaeologists

Peat moss around a pool in Cairngorms National Park in the United Kingdom

DUNCAN SHAW/SCIENCE SOURCE

The wrinkles on the face of “Tollund Man” are still visible, even though he died more than 2200 years ago. The mossy wetlands in Denmark that mummified his body are ideal for preserving organic matter, giving archaeologists an extraordinary window into our distant past. But a recent excavation at a similarly boggy site in Sweden shows these perfect conditions are fragile, and when they break down, so, too, do the bodies, bones, and other organic remains that have been preserved for centuries. The finding suggests a long-standing tenet of archaeology—avoiding excavation and leaving artifacts in the ground for long-term preservation—needs revisiting, at least for some wetland sites.

Anecdotal evidence has long suggested the condition of remains excavated from wetlands like peat bogs is declining, says Benjamin Gearey, a wetland archaeologist at University College Cork who was not involved with this study. For example, bone deterioration has been documented at Star Carr, an archaeological site in northern England. But it’s been hard to know how widespread the pattern is–and how fast the decay is occurring.

Ageröd, a peat bog in the south of Sweden that holds bones, antlers, and other artifacts from Mesolithic cultures that flourished more than 8000 years ago, is a good place to measure the pace of decay in a peat bog, says Adam Boethius, an archaeologist at Lund University. Boethius and his colleagues compared bones freshly excavated in 2019 with bones that had been exhumed from the bog in the 1940s and 1970s and stored in the Lund University Historical Museum. They rated the weathering of each bone, from well-preserved ones—those that were shiny and crack-free—to dull bones with worn outer surfaces.

Read the rest of this article...

New Roman fort uncovered in Lancashire after years of speculation

A Roman fort lies underneath land off Flax Lane, Burscough

Historic England says the lines of the fort’s defences are clearly identifiable on geophysical survey and aerial photos

A 1st Century fort uncovered at a Burscough farm could be the key to understanding Roman activity in Lancashire.

After years of speculation about the presence of such a fort, ruins off Flax Lane have finally received recognition from Historic England.

The ruins comprise a 30,000 sq m fort, roads, and a smaller fortlet and experts believe the find will unlock unknown details of how the Romans settled and travelled around the area. Considered alongside other forts in the region, including those at Wigan and Ribchester, Burscough’s will provide great insight into Roman military strategy. It is believed that the area was occupied multiple times over the course of hundreds of years, a theory which is backed up by the variety of pottery found at the site.

Historic England says the lines of the fort’s defences are clearly identifiable on geophysical survey and aerial photos, but the north-west and south-west corners are also visible as slight earthworks on Lidar, which uses laser light reflections to produce 3D images.

Read the rest of this article...

Discovery of 26 skeletons in front garden to shed new light on ancient island life

Scalloway on Shetland close to where the human remains were found. PIC: Tom Parnell/Creative Commons.

The discovery of 26 skeletons in a front garden in Shetland is set to shed new light on ancient life in Scotland’s most northerly isles.

The human remains, which were likely laid to rest aroud 500 to 600 years ago, were found in Upper Scalloway on the Shetland mainland after a homeowner started digging to build a shed for his children’s bikes.

It is believed the skeletons were buried on land which formed part of an Iron Age Village, which was first discovered in the 1980s and centred round a broch, or a large stone tower.

Earlier Pictish-era finds, including painted pebbles and a bone comb, were also discovered at the site indicating that it was occupied some 600 years before the Iron Age settlement took shape.

Val Turner, archaeologist with the Shetland Amenity Trust, said the remains could shed new light on life in Shetland through time, with advances in archaeological science set to offer up new information about those living on the islands hundreds of years ago.

Read the rest of this article...

The discovery of 26 skeletons in a front garden in Shetland is set to shed new light on ancient life in Scotland’s most northerly isles.

The human remains, which were likely laid to rest aroud 500 to 600 years ago, were found in Upper Scalloway on the Shetland mainland after a homeowner started digging to build a shed for his children’s bikes.

It is believed the skeletons were buried on land which formed part of an Iron Age Village, which was first discovered in the 1980s and centred round a broch, or a large stone tower.

Earlier Pictish-era finds, including painted pebbles and a bone comb, were also discovered at the site indicating that it was occupied some 600 years before the Iron Age settlement took shape.

Val Turner, archaeologist with the Shetland Amenity Trust, said the remains could shed new light on life in Shetland through time, with advances in archaeological science set to offer up new information about those living on the islands hundreds of years ago.

Read the rest of this article...

Hundreds of arrowheads and crossbow bolts found in Polish forest

Credit: Historical Museum in Sanok

Hundreds of arrowheads and crossbow bolts thought to have come from Casimir the Great’s 1340 attack on the lands of Galicia which as a result became part of Poland have been discovered in a forest in Sanok.

Known as the 'Castle', the stronghold is located on one of the forested peaks of the Słonne Mountains - Biała Góra, part of the Sanok district of Wójtostwo.

Until recently, the place was a mystery to scientists, because the only major archaeological research in the area was carried out half a century ago. But following a spate of illegal treasure hunts in the area, archaeologists decided to investigate.

Head of the research project, Dr. Piotr Kotowicz from the Historical Museum in Sanok said: “The results exceeded our wildest expectations. During several seasons, in and around the stronghold, we found over 200 arrowheads and crossbow bolts used.”

The objects come from the middle of the 14th century and according to Dr. Kotowicz is not a coincidence. During that period the area was taken over by the Polish king Casimir the Great, which happened as a consequence of the death of Bolesław Trojdenowicz, the last prince of Ruthenian Galicia.

Read the rest of this article...

Stonehenge: Sarsen stones origin mystery solved

The origin of the standing sarsens at Stonehenge had been impossible to identify until now

The origin of the giant sarsen stones at Stonehenge has finally been discovered with the help of a missing piece of the site which was returned after 60 years.

A test of the metre-long core was matched with a geochemical study of the standing megaliths.

Archaeologists pinpointed the source of the stones to an area 15 miles (25km) north of the site near Marlborough.

English Heritage's Susan Greaney said the discovery was "a real thrill".

The seven-metre tall sarsens, which weigh about 20 tonnes, form all fifteen stones of Stonehenge's central horseshoe, the uprights and lintels of the outer circle, as well as outlying stones.

Read the rest of this article...

The Romans Called it ‘Alexandrian Glass.’ Where Was It Really From?

Glass receptacles recovered from Egypt dating to the first or second century A.D., during the Roman occupation. Credit...Artokoloro, via Alamy

Trace quantities of isotopes hint at the true origin of a kind of glass that was highly prized in the Roman Empire.

Glass was highly valued across the Roman Empire, particularly a colorless, transparent version that resembled rock crystal. But the source of this coveted material — known as Alexandrian glass — has long remained a mystery. Now, by studying trace quantities of the element hafnium within the glass, researchers have shown that this prized commodity really did originate in ancient Egypt.

It was during the time of the Roman Empire that drinks and food were served in glass vessels for the first time on a large scale, said Patrick Degryse, an archaeometrist at KU Leuven in Belgium, who was not involved in the new study. “It was on every table,” he said. Glass was also used in windows and mosaics.

All that glass had to come from somewhere. Between the first and ninth centuries A.D., Roman glassmakers in coastal regions of Egypt and the Levant filled furnaces with sand. The enormous slabs of glass they created tipped the scales at up to nearly 20 tons. That glass was then broken up and distributed to glass workshops, where it was remelted and shaped into final products.

Read the rest of this article...

Archaeological dig on the A1 in North Yorkshire uncovers Roman remains

Archaeologists at work near Scotch Corner

Archaeologists excavating the A1 before the road's major upgrade have discovered fascinating evidence of Roman engineering and repair work.

The dig between Leeming Bar and Barton, near Scotch Corner, revealed that the Romans settled in North Yorkshire at least a decade earlier than previously thought. They produced coins for circulation and built relationships with the local tribes.

The modern A1 partly follows the route of Roman roads between York and Hadrian's Wall that were used mainly for the movements of legions based at the York garrison who were deployed to subdue the border regions.

Highways England, who oversaw the archaeological work ahead of the upgrade of the A1(M), believe the finds in the vicinity of Scotch Corner are among the best discoveries of the past decade, and a book about the excavations has now been published.

Read the rest of this article...

Study Suggests Bones Preserved in Peat Bogs May Be at Risk

Bogs are perhaps best known for preserving prehistoric human remains. One of the most famous examples of these so-called "bog bodies" is Tollund Man. (Getty Images)

Per the paper, archaeologists need to act quickly to recover organic material trapped in the wetlands before specimens degrade

Peat bogs are notoriously uninhabitable. When low in oxygen, they don’t support microbial life, and without microbes, dead humans and animals caught in the spongy wetlands fail to decompose. Thanks to this unusual characteristic, peat bogs have long been the scene of incredible archaeological discoveries, including naturally mummified human remains known as bog bodies.

But new research published in the journal PLOS One presents evidence that bogs are losing their body-preserving abilities. As Cathleen O’Grady reports for Science magazine, archaeologists found that the best-preserved artifacts recovered from bogs in 2019 resemble the worst-preserved ones found in the 1970s, while the best-preserved specimens from the ’70s are on par with the worst retrieved in the 1940s. (Bogs’ lack of oxygen, as well as an abundance of weakly acidic tannins, preserves artifacts as delicate as small mammal and bird bones.)

The findings suggest that archaeologists may need to act quickly to uncover what’s left in the world’s bogs.

“If we do nothing, wait and hope for the best, it is likely that the archaeo-organic remains in many areas will be gone in a decade or two,” the authors say in a statement. “Once it is gone there is no going back, and what is lost will be lost forever.”

Northern Europe is dotted with peat bogs, which stood out among the thickly forested prehistoric landscape and may have served as spiritual places. “Half earth, half water and open to the heavens, they were borderlands to the beyond,” wrote Joshua Levine for Smithsonian magazine in 2017.

Many bog bodies show signs of horrific violence. Theories regarding these unlucky individuals’ deaths—and unusual mode of interment—range from execution to robberies gone wrong and accidents, but as archaeologist Miranda Aldhouse-Green told the Atlantic’s Jacob Mikanowski in 2016, the most likely explanation is that these men and women were victims of ritualized human sacrifice.

Read the rest of this article...

Neanderthal Genetics May Explain Your Low Tolerance for Pain

NURPHOTOGETTY IMAGES

Turns out your eldest ancestors sexual antics might be the reason you’re especially sensitive to painful stimuli.

If you have a low tolerance for pain new research suggests you should blame it on our Neanderthal cousins.

According to joint research from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany and Sweden’s Karolinska Institutet, “people who inherited a special ion channel from Neanderthals experience more pain.”

In their paper, the researchers describe Nav1.7, a sodium channel “crucial for impulse generation and conduction in peripheral pain pathways,” which showed reduced inactivation in Neanderthals. Researchers deduced that because of this lowered level of activation, Neanderthals experienced heightened pain sensitivity in comparison to modern humans.

Read the rest of this article...

Archaeology Take a tusk, drill holes, weave a rope – and change the course of history

he fragments found at Hohle Fels cave in Germany that scientists now recognise as a rope-making tool from 40,000 years ago. Photograph: University of Tübingen

Scientists have discovered the tool our stone-age ancestors used to manufacture twine – a milestone in technological development

Forty thousand years ago, a stone-age toolmaker carved a curious instrument from mammoth tusk. Twenty centimetres long, the ivory strip has four holes drilled in it, each lined with precisely cut spiral incisions.

The purpose of this strange device was unclear when it was discovered in Hohle Fels cave in south-western Germany several years ago. It could have been part of a musical instrument or a religious object, it was suggested. But now scientists have concluded that it is the earliest known instrument for making rope. And its impact would have been revolutionary.

Our stone-age ancestors would have been able to feed plant fibres through the instrument’s four holes and by twisting it create strong ropes and twines. The grooves round the holes would have helped keep the plant fibres in place.

Read the rest of this article...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

:focal(3042x1756:3043x1757)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/e7/8b/e78ba0c2-264f-4bba-97c8-2281d02fa3df/gettyimages-599000988.jpg)