Images of the early medieval sword as well as an X-ray image. (Image credit: O. Ochotny)

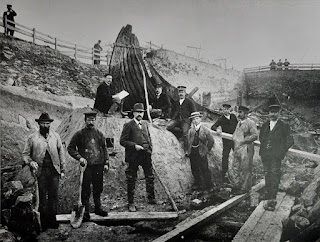

Workers made a surprising discovery in Poland when they pulled an early medieval sword from a muddy riverbed while dredging, and some researchers think the weapon could have a Viking connection.

The 1,000-year-old sword, which is thought to be older than Poland itself, was found cloaked in silt and in "near perfect" condition in the depths of the Vistula (also spelled Wisła) River, which runs through Włocławek, a city in northern Poland, according to Warsaw Point, a Polish magazine.

Local authorities contacted the Provincial Office for the Protection of Monuments about the unusual finding. The city’s Center for Sport and Recreation announced the discovery Jan. 12 via a Facebook post.

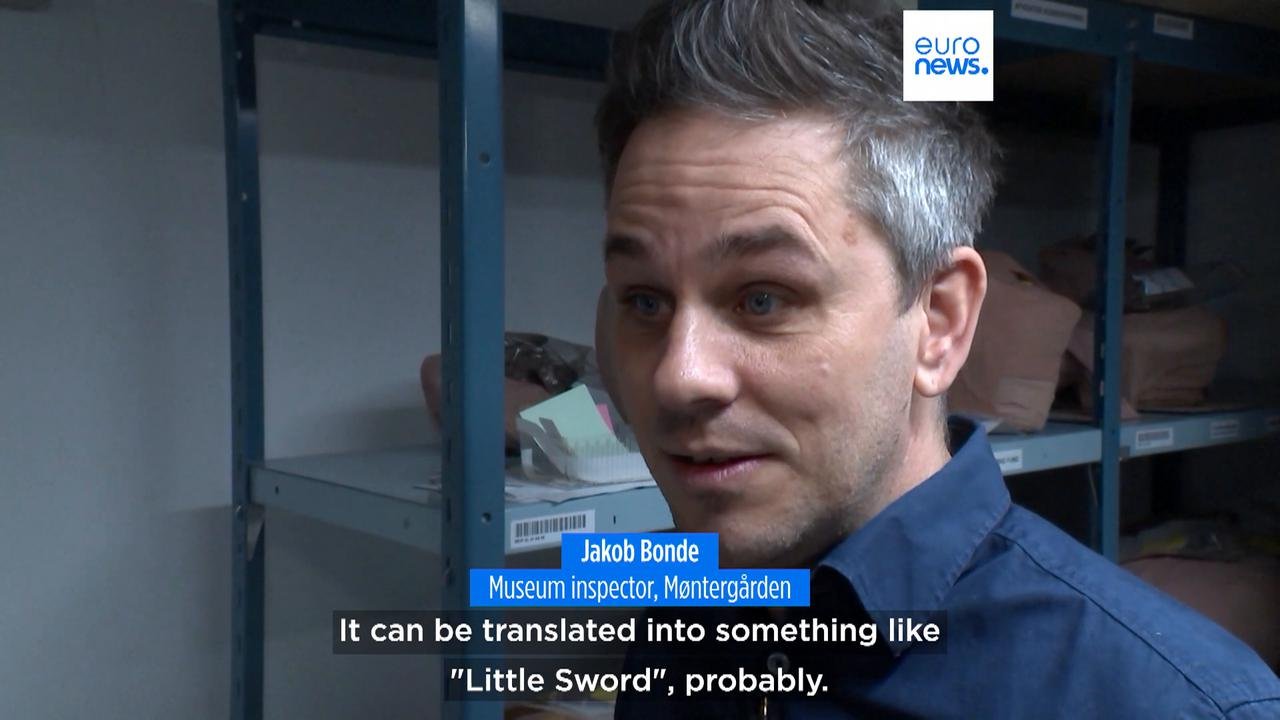

X-ray imaging revealed that the sword's blade contained an inscription that reads "U[V]LFBERTH," which could be read as "Ulfberht" — "a marking found on a group of 170 medieval swords found mainly in northern Europe" that may be a Frankish personal name, according to CBS News.

Read the rest of this article...

:focal(640x482:641x483)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/27/7127f22f-29d3-49e2-a799-c71687a21c02/face_lead_image.jpeg)