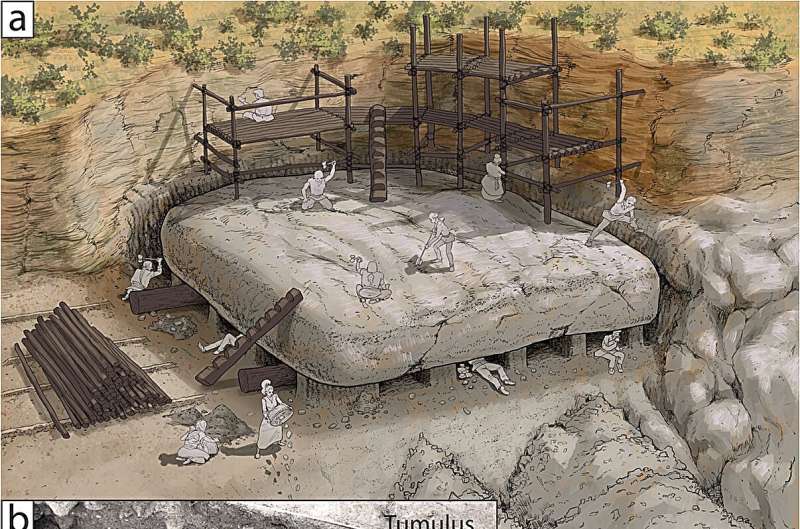

Archaeologists at work uncovering evidence of a battle that was fought in the Julier Valley around 15 B.C.E. image: Archaeological Service Graubünden

oday, the Julier Valley in Switzerland is an idyllic place with majestic mountains and wide, green fields. But some 2,000 years ago, archaeologists now believe that it was the site of a fierce battle between Roman soldiers and local warriors, one which changed the course of history and helped lead to the Roman occupation of modern-day Switzerland.

During the examination of the site, which is located in the Crap-Ses gorge between the towns of Tiefencastel and Cunter, archaeologists have found thousands of objects that allude to the valley’s violent past. These include swords, slingshot bullets, brooches, coins, fragments of shields, and thousands upon thousands of Roman hobnails, which were hammered into the soles of leather boots and shoes.

There is so much at the site, in fact, that archaeologists uncovered an average of 250 to 300 objects per day during a three-week period in the autumn.

Read the rest of this article...

:focal(450x315:451x316)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/89/68/89689564-c0d6-4e1d-ac17-590973b16b25/marketscene-900x627.jpeg)