Monday, May 07, 2018

Scientists Confirm Earliest Use of Fire and Oldest Stone Handaxe in Europe

In a recently published paper* in the journal, Historical Biology, researchers report confirmation that sediments bearing early human cultural remains in the Cueva Negra del Estrecho del Río Quípar rockshelter in southeastern Spain are dated to over 800,000 years ago. The sediments include an Acheulean style stone handaxe and evidence for the use of fire within the rockshelter.

“We regard its age as quite likely between 865,000 and 810,000 years ago,” said Michael Walker of Spain’s Murcia University, a lead researcher on Cueva Negra.

“[Arguably] Until now hand-axes in Europe have not been recorded from before 500,000 years ago,” said Walker. Moreover, he adds, “the evidence of combustion [use of fire] is also the oldest anywhere outside Africa.”

Read the rest of this article...

Roman relics found in Rhine region show evidence of bloody uprising

One of the ancient Roman helmets found in the recent excavation in Krefeld. Photo: DPA

In the North Rhine-Westphalian town of Krefeld, a recent archaeological dig revealed thousands of ancient relics. These finds tell the story of the region’s turbulent Roman history.

Tens of thousands of artefacts were dug out of sand and clay near the Rhine, archaeologists in Krefeld announced in April.

A recent 10-month excavation along the Rhine revealed a wealth of previously-unseen Roman ruins, including hundreds of coins, weapons, horse skeletons, jewellery, helmets, and the artfully decorated belt buckle of a soldier. Packed in boxes, the relics span over 75 cubic metres.

In the small town just outside Düsseldorf, nearly 6,500 graves were found dating from between 800 BC and 800 AD, which often contained valuable burial objects. It is one of the largest ancient cemeteries north of the Alps.

Read the rest of this article...

Stone Age settlement found in the middle of Copenhagen

Traces of Copenhagen’s Stone Age past were found under the resistance museum just opposite the Anglican church (photo: Henrik Lundbak, Nationalmuseet)

Archaeologists from the Museum of Copenhagen have made a rather sensational discovery: evidence of a settlement estimated to be around 7,000 years old.

During the building work for the new museum of Danish resistance at Kastellet, flint arrowheads, animal bones and even a couple of human bones have come to light, a municipal press release reveals.

“Finding a Stone Age settlement is special because it reveals the history of the area long before it became Copenhagen,” said the deputy mayor for culture and leisure, Niko Grünfeld.

Read the rest of this article...

Iron Age finds to go on display in Alderney

A display of Iron Age finds that were dug up in Alderney are going on display in the island.

Guernsey Museums is also heading back to the island in July to carry out three archaeological excavations at the Nunnery, a Roman gate and a cemetery.

Dr Jason Monaghan, head of heritage services at Guernsey Museums, said the Iron Age finds were of a "really high quality for such a small place".

"This must mean it was an important place - we think the trade routes may have come right past Alderney," he added.

Read the rest of this article...

Beowulf: The enduring appeal of an Anglo-Saxon 'superhero story'

Beowulf is the oldest surviving epic poem in the English language

As the cold sting of winter finally starts to fade, so the literary festival season edges closer. An addition to the line-up this year is a five-day celebration of the legendary saga of Beowulf. How is it that a story written by an unknown author more than 1,000 years ago still captures the imagination?

The eponymous hero of this 3,182-line poem battles fierce monsters, rips off his enemy's arm, fights a fire-breathing dragon and defends a nation.

It could be the plot of Hollywood's latest blockbuster movie.

But this is the story of Beowulf, a poem once told in timber-framed barns in Anglo-Saxon England, to the raucous noise of the mead-swilling crowd.

Described by historian and broadcaster Michael Wood as "being at the very root of English literature", the author and the exact date of composition remain a mystery.

Read the rest of this article...

Meet the ancestors… the two brothers creating lifelike figures of early man

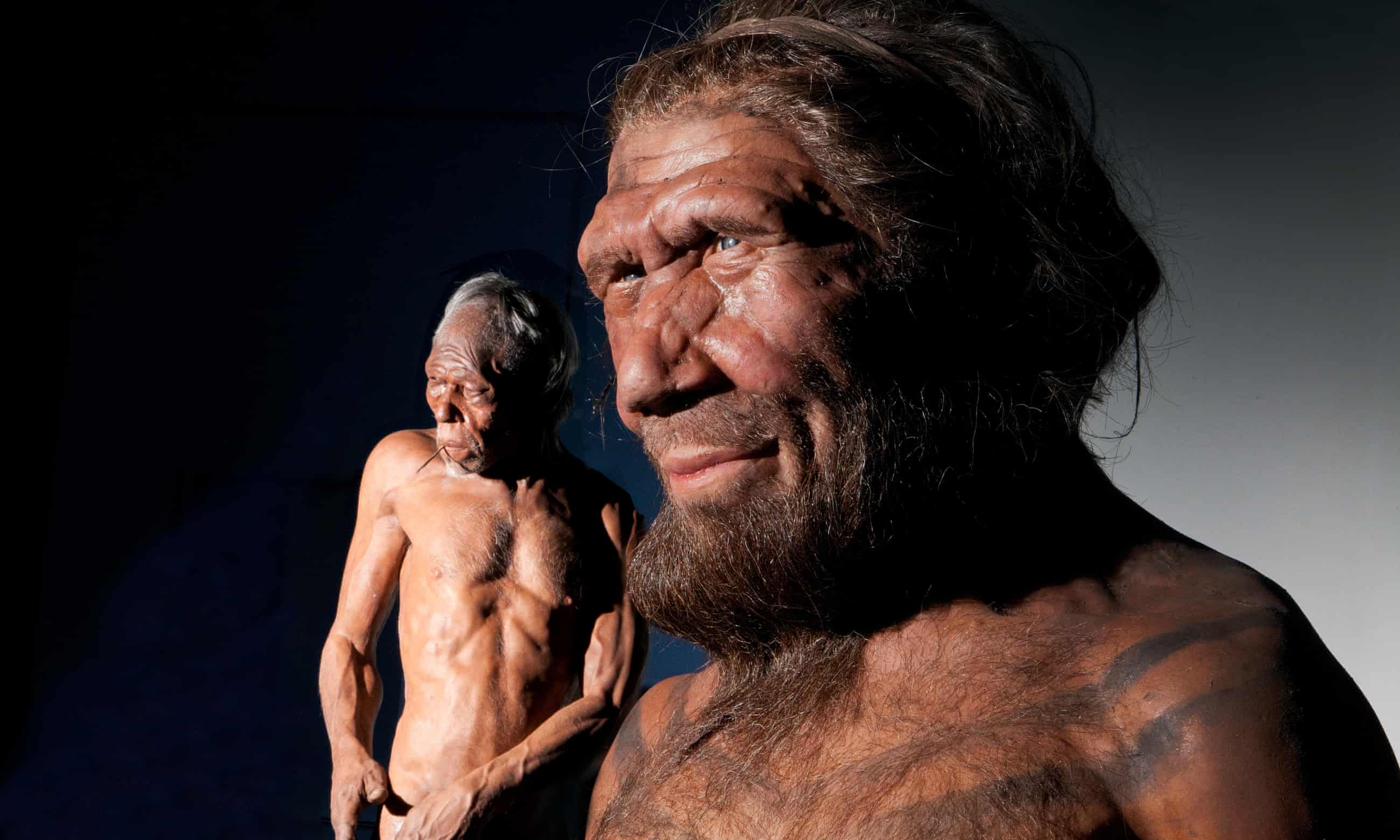

Compare and contrast (l-r): Homo sapiens and a Neanderthal man. Photograph: Kevin Webb/

The Natural History Museum, London

Dutch twins Adrie and Alfons Kennis are showing their uncanny models in museums all over Europe. Adrie discusses how their creations are realised and the extreme reactions they can provoke

Identical twins with a combined age of 102, Adrie and Alfons Kennis are among Europe’s most sought-after – and controversial – hominid palaeo-artists: sculptors of lifesize reconstructions of early humans.

Working from a studio in their home town of Arnhem in the Netherlands, the brothers bring a surplus of exuberance to their creations, which are richly animated, expressive and – how better to put it? – human, even when they aren’t quite human. “If we have to make a reconstruction,” says Adrie, “we always want it to be a fascinating one, not some dull white dummy that’s just come out of the shower.”

In the 10 or so full-sized reconstructions completed during their career they have run the gamut of human history, from “Lucy” – the earliest known hominin fossil – to Homo erectus, Neanderthal man and, of course, Homo sapiens. Just last week, they put the finishing touches to a model for St Fagans National Museum of History in Wales. Due to be unveiled in October, it will be the third Kennis & Kennis work on display in the UK.

The process is exhausting. First, they rebuild the skeleton, sometimes using fossils from several different sites, with the help of computer scans and 3D printing. The skeleton is suspended with wire cables and the spine is made flexible using silicone cartilage between the vertebrae. “We use a kind of paraffin wax clay to sculpt the muscles,” says Adrie, “and we make arteries using small ropes which lie over the muscles.” Layers of another clay are then wrapped around the sculpture as skin, and a mould is made to replicate the sculpture in silicone. “We do five layers of silicone to make the skin colour,” explains Adrie, “because real skin is translucent.”

Read the rest of this article...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)