Archaeologists have discovered the oldest and most complete Roman body armour at the site of the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in Kalkriese, Germany. Before this find, the earliest known examples of Roman lorica segmentata — iron plate sections tied together — were found in Corbridge, UK, and date to the 2nd century. Those were fragments. The Kalkriese armor is a complete set, and includes an extremely rare iron collar used to shackle prisoners.

More than 7,000 objects have been found at the Kalkriese battlefield site, from weapons to coins to items of everyday use. In the summer of 2018, a metal detector scan of the side wall of an excavation trench retuned 10 strong signals, indications of a large quantity of metal inside the bank. To ensure whatever was in there wasn’t exposed to the air and rapid oxidization, archaeologists removed the entire soil block containing the mystery metallics.

The first step was to scan the block to see what was inside and map out its excavation. The block was too big for regular X-ray machines, so they transported the crate to the Münster Osnabrück International Airport where the customs office has a freight-sized X-ray machine. All they could see was nails of the wooden crate and a large black hole in the shape of the soil block.

In 2019, it was sent to the Fraunhofer Institute in Fürth which has the world’s largest CT scanner — a circular platform more than 11 feet in diameter that rotates while the X-ray apparatus moves up and down — more than big enough for the crate to fit and powerful enough to see inside the dense soil block. The scan revealed the remains of a cuirass — the section of a lorica segmentata where the breastplate and back plate are buckled together. The plates of the armour were pushed together like an accordion by the weight of the soil pressing on down them for 2,000 years.

Here’s a nifty digital animation by the Fraunhofer Institute generated from the CT scan data that reveals the armour inside the soil block.

Armed with the detailed scans, restorers were able to begin excavation of the soil block. They found that despite Kalkriese’s highly acidic sandy soil, the armour is relatively well-preserved. There is extensive corrosion of the mental, but the set is uniquely complete with hinges, buckles, bronze bosses and even extremely rare surviving pieces of the leather ties. The plates from the shoulder and chest have been recovered and restored. The belly plates are still in the soil block. There are no arm plates in this early design.

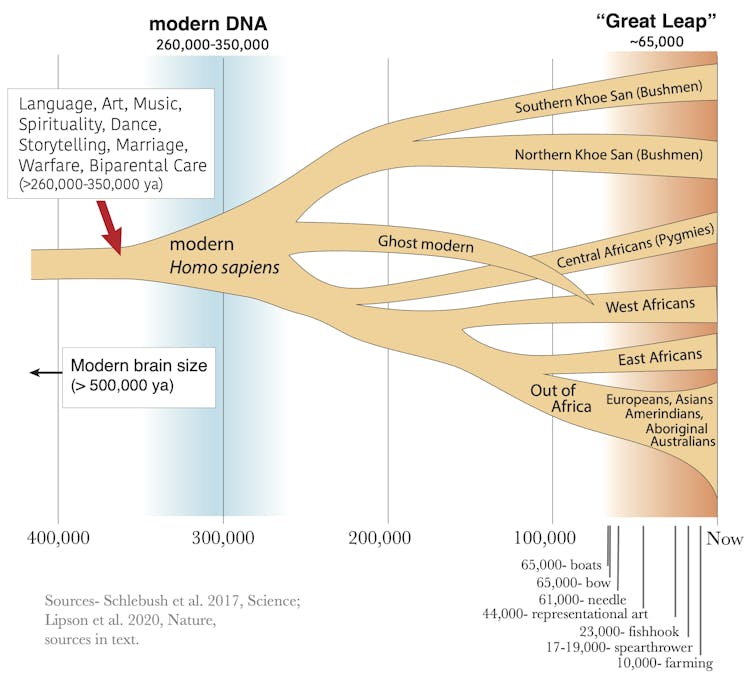

Iron plate armour was introduced by Augustus as an improvement on chain mail. It was relatively light (around 17 pounds) and because the plates were tied together with leather cords, they were much more flexible than chain mail. so it was the latest and greatest technology in 9 A.D. when Publius Quinctilius Varus blundered into a German ambush that obliterated three full Roman legions plus their auxiliaries.

The legionary who wore this armour apparently survived the battle because around his neck/shoulder area was a shrew’s fiddle, also known as a neck violin. This was an iron collar connected to two handcuffs that locked a prisoner’s hands in front of his neck. The Romans used them to shackle prisoners destined for slavery. This time the tables were turned, and the soldier died in shackles.

The restoration is ongoing and is expected to take another two years. Once it’s complete, the armour will go on display in an exhibition at the Kalkriese Museum and Park.

:focal(2611x1667:2612x1668)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/9b/c6/9bc6d247-2de8-4f9c-8bf1-4daa804253dd/pxfuelcom.jpg)