Archaeologists have found evidence of ancient human activity on Britain’s very own “Atlantis”.

Scientists investigating a drowned Stone Age landscape at the bottom of the North Sea have discovered two potential prehistoric settlement sites on the banks of a long-vanished ancient river.

It is the first time that an archaeological expedition has ever found such evidence far offshore under the huge body of water.

In the past, prehistoric artefacts have on occasions been trawled up by fishermen and found by oil exploration teams – but the seabed contexts they came from were never archaeologically assessed.

This time, the discoveries are part of a systematic archaeological survey.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, June 17, 2019

Archaeologists discover that Roman dockers ate surprisingly well – until the barbarians arrived

Built during the reign of Claudius in the 1st century AD at the mouth of the Tiber,

Portus was the epicentre of Roman trade for centuries.

Portus was the epicentre of Roman trade for centuries.

(Photo: Portus Project/Artas Media)

British-led study finds that all inhabitants of the town of Portus had a similar diet rich in meat and North African wine

Ancient Rome may have not have had much to offer its subjects by way of equality but when it came to the diet of its dockers at least it seems they dined something like emperors.

A British-led archaeological study of remains found in Portus, the maritime port which served Rome, has found that its labouring inhabitants benefited from the flow of goods through the town by having a diet entirely similar to that of its wealthy ruling citizens – at least until the “barbarians” arrived.

Exotic goods

The study, based on an analysis of food and human remains at locations around the manmade port to the west of Rome, found that dockers or “saccarii” benefited from their work unloading the flow of exotic goods – including bears and crocodiles – to the heart of the ancient empire with a diet rich in animal protein, imported wheat, olive oil and wine from North Africa.

Comparison with remains found at locations where rich and middle class inhabitants lived during the second to the fifth centuries AD found the same sort of diet, suggesting that Portus was unusual in the Roman world in that rich and poor ate similarly well.

Read the rest of this article...

Anglesey archaeology: Bronze Age cairn dig at Bryn Celli Ddu

Bryn Celli Ddu burial chamber is aligned to the sun and is lit during the summer solstice

AERIAL-CAM

An excavation is under way on the site of a suspected 4,500-year-old burial cairn that lies next to one of Wales' most important prehistoric monuments.

Experts are hoping to learn more about it and its relationship to Bryn Celli Ddu burial chamber at Anglesey.

The 5,000-year-old "passage tomb" is aligned to coincide with the rising sun on the summer solstice.

Dr Ffion Reynolds said the cairn showed the site remained a "special location" centuries after the chamber was built.

Read the rest of this article...

Sunday, June 16, 2019

Archaeologists uncover megalithic monument thought to be unlike any found in Ireland to date

IT Sligo Archaeology students Jazmin Scally Koulak and Eugene Anderson sieving the soil at Carrowmore excavation

AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATION in Co Sligo has uncovered a megalithic monument thought to be unlike any found in Ireland to date.

Several prehistoric tools made from a hard stone called chert were discovered and are thought to have been used for activities such as working animal hides, cutting and preparing food, basket food, basket working and bone working.

The discovery was made by a team of archaeologists from IT Sligo during a two-week excavation of a prehistoric monument in the heart of the Carrowmore megalithic complex in Co Sligo.

Carrowmore in the largest cemetery of megalithic tombs in Ireland, with 5,500-year-old passage tombs dating from 3,600 BC.

Read the rest of this article...

Thursday, June 13, 2019

Artificial islands older than Stonehenge stump scientists

A diver holds a Neolithic (ca. 3,500 B.C) Ustan vessel found near a crannog (artificial island)

in Loch Arnish, Scotland. PHOTOGRAPH BY C. MURRAY

When it comes to studying Neolithic Britain (4,000-2,500 B.C.), a bit of archaeological mystery is to be expected. Since Neolithic farmers existed long before written language made its way to the British Isles, the only records of their lives are the things they left behind. And while they did leave us a lot of monuments that took, well, monumental effort to build—think Stonehenge or the stone circles of Orkney—the cultural practices and deeper intentions behind these sites are largely unknown.

Now it looks like there may potentially be a whole new type of Neolithic monument for archaeologists to scratch their heads over: crannogs.

Artificial islands commonly known as crannogs dot hundreds of Scottish and Irish lakes and waterways. Until now, researchers thought most were built when people in the Iron Age (800-43 B.C.) created stone causeways and dwellings in the middle of bodies of water. But a new paper published today in the journal Antiquity suggests that at least some of Scotland’s nearly 600 crannogs are much, much older—nearly three thousand years older—putting them firmly in the Neolithic era. What’s more, the artifacts that help push back the date of the crannogs into the far deeper past may also point to a kind of behavior not previously suspected in this prehistoric period.

Read the rest of this article...

Britain’s best places to see: Roman heritage sites

St. Mary in Castro, Dover Castle, Dover +Roman lighthouse © milo bostock (CC BY-SA 2.0)

What’s a medieval castle, founded only in the 11th century, got to do with the Romans? Being the British mainland’s closest point to Continental Europe, Dover has consistently been an important base for trade, travel and defence, and it is thought that the use of the site now occupying Dover Castle may have been utilised from as early as the Iron Age. What is known about the early origins of the site was that it was used by the Romans – evidenced by a rather unique structure in its grounds, adjacent to the St Mary in Castro church.

Constructed sometime during the 2nd century AD, when Dover was known as Dubris, this stone tower is a Roman pharos, or lighthouse, and is the most complete Roman structure standing in Britain. The 8-sided tower is something really rather special, with only three examples of Roman lighthouses existing anywhere in the world (another of which is also in Dover, though only a small section remains).

Read the rest of this article...

Ancient DNA from Roman and medieval grape seeds reveal ancestry of wine making

Statue of Dionysus (Bacchus), god of wine (stock image).

Credit: © Ruslan Gilmanshin / Adobe Stock

A grape variety still used in wine production in France today can be traced back 900 years to just one ancestral plant, scientists have discovered.

With the help of an extensive genetic database of modern grapevines, researchers were able to test and compare 28 archaeological seeds from French sites dating back to the Iron Age, Roman era, and medieval period.

Utilising similar ancient DNA methods used in tracing human ancestors, a team of researchers from the UK, Denmark, France, Spain, and Germany, drew genetic connections between seeds from different archaeological sites, as well as links to modern-day grape varieties.

Read the rest of this article...

Friday, June 07, 2019

DNA from 31,000-year-old milk teeth leads to discovery of new Ice Age population of big game hunters

The DNA was recovered from the only human remains discovered during the era – two tiny milk teeth ( Russian Academy of Sciences )

A new Ice Age population of big game hunters that lived in the depths of Siberia has been discovered using DNA taken from 31,000-year-old human milk teeth.

Named the ‘Ancient North Siberians’ the hardy population would have hunted lions, wolves, woolly mammoths and bison, according to a study led by Cambridge University.

The find was one aspect of new research into the genetic composition of Native Americans who in part descended from these Siberian hunters.

The existence of this fierce population, who first evolved 38,000 years ago, forms “a significant part of human history”, according to lead researcher Professor Eske Willerslev.

He told The Independent: “These humans had adapted to an extremely harsh environment in terms of temperatures – it’s a part of the world that is almost completely dark all winter. There are basically no trees and they were living alongside lions, wolves, bison and rhinos.

Read the rest of this article...

Second oldest church in Germany uncovered

The site in the foundation of the church where human remains have also been found.

Photo: DPA

Archaeologists have discovered Germany’s second oldest church hidden within a cathedral in the west of the country.

In the so-called "Old Cathedral" in Mainz, which is today the evangelical Church of St John, archaeologists found the remains of another church built 1,200 years ago in the time of Charlemagne, Deacon Andreas Klodt said on Tuesday.

Only Trier on the Mosel River has an older church, with its cathedral dating back to Roman times, making the find the second oldest church in the country.

Professor Matthias Untermann from the Institute of Art History in Heidelberg said the remains of the Carolingian walls stretched from the basement to the roof.

Read the rest of this article...

Thursday, June 06, 2019

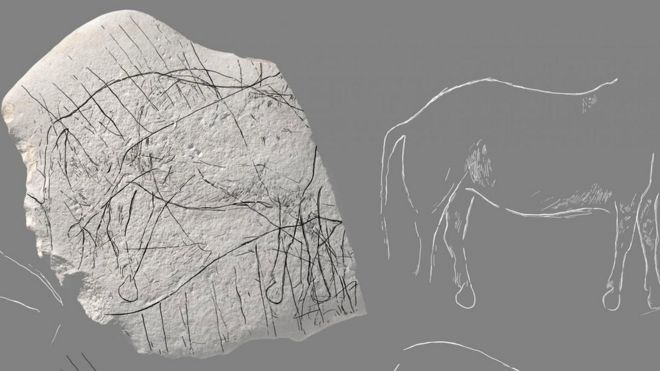

Prehistoric stone engraved with horses found in France

A generated image of the prehistoric sandstone plate and its engraving

DENIS GLIKSMAN/INRAP

A stone believed to be about 12,000 years old and engraved with what appears to be a horse and other animals has been discovered in France.

The prehistoric find by archaeologists excavating a site in the south-western Angoulême district, north of Bordeaux, has been described as "exceptional".

Markings appear on both sides of the sandstone, the National Archaeological Research Institute (Inrap) said.

It was found during work at an "ancient hunting site" near Angoulême station.

The Palaeolithic stone plate, which is said to be about 25cm long, 18cm wide and 3cm thick, "combines geometric and figurative motifs", Inrap said.

Read the rest of this article...

Incredibly rare ancient map of London is discovered from 1572 – and the roads are the same

The map shows little life to the south of the river, but the city is already full of winding streets (Picture: BNPS)

An extremely rare example of the earliest surviving map of London has been discovered. The 1572 city plan, by engraver Frans Hogenburg, provides a fascinating bird’s eye view of the underdeveloped capital city.

It reveals there was a large settlement north of the River Thames, but south of it was sparsely populated. T

he colourful map depicts many boats weaving their way down the river, which could only be crossed by the solitary Old London Bridge.

Recognisable landmarks include the Tower of London, the Charterhouse monastery and the old St Paul’s Cathedral, while Westminster is marked as ‘West Mester’.

In a nod to a bygone age, bear baiting is shown in Southwark, and there are drawings of Queen Elizabeth figures around the map’s edges.

Wednesday, June 05, 2019

Africa’s first herders spread pastoralism by mating with foragers

INHERITING HERDING Ancient DNA indicates that early African herders started mating with hunter-gatherers more than 5,000 years ago. Here, modern herders in Tanzania watch over their goats.

Ancient sheep, goat and cattle herders made Africa their home by hooking up with the continent’s native hunter-gatherers, a study suggests.

DNA analysis shows that African herders and foragers mated with each other in two phases, says a team led by archaeologist Mary Prendergast of Saint Louis University in Madrid. After entering northeastern Africa from the Middle East around 8,000 years ago, herders swapped DNA with native foragers between roughly 6,000 and 5,000 years ago. Herders possessing some forager heritage then trekked about halfway down the continent and mated with eastern African foragers around 4,000 years ago, the scientists report online May 30 in Science.

Present-day herders, such as the Dinka in South Sudan, still live in eastern Africa. But how pastoralism spread into the region has been a mystery. In particular, it has been difficult to tell whether ancient African hunter-gatherers mated with early herders or simply adopted their livestock practices. The new study supports an emerging view from ancient DNA studies that human cultural evolution has often featured mating across groups with different traditions and lifestyles.

Read the rest of this article...

Monday, June 03, 2019

Long-lost Lewis Chessman found in Edinburgh family's drawer

A medieval chess piece that was missing for almost 200 years had been unknowingly kept in a drawer by an Edinburgh family.

They had no idea that the object was one of the long-lost Lewis Chessmen - which could now fetch £1m at auction.

The chessmen were found on the Isle of Lewis in 1831 but the whereabouts of five pieces have remained a mystery.

The Edinburgh family's grandfather, an antiques dealer, had bought the chess piece for £5 in 1964.

He had no idea of the significance of the 8.8cm piece (3.5in), made from walrus ivory, which he passed down to his family.

They have looked after it for 55 years without realising its importance, before taking it to Sotheby's auction house in London.

Read the rest of this article...

Byzantine Constantinople, the navel of the (medieval) world

Byzantine Constantinople, the navel of the (medieval) world

A Lecture by Dr Aphrodite Papayianni

7.00pm Friday, 7 June 2019

at the Museum of London

Further details...

Lewis chessmen piece bought for £5 in 1964 could sell for £1m

The newly discovered medieval Lewis warder chess piece was missing for almost 200 years. Photograph: Tristan Fewings/Sotheby's/PA

A small walrus tusk warrior figure bought for £5 in 1964 – which, for years, was stored in a household drawer – is a missing piece from one of the true wonders of the medieval world, it has been revealed.

The Lewis chessmen were found in 1831 in the Outer Hebrides and became beloved museum collections in London and Edinburgh. They have also become well known in popular culture from Noggin the Nog to Harry Potter.

But of the 93 pieces found, five were known to be missing. Until now. On Monday the auction house Sotheby’s announced it had authenticated a missing piece and would sell it in July with an estimated value of between £600,000 and £1m.

The missing piece, measuring 8.8cm in height, is a Lewis warder and – 55 years ago – was purchased for £5, about £100 in today’s money.

Read the rest of this article...

The Birdman of Siberia: sensational finds in the heart of Russia puzzle scientists

Two unique burials of the Odinov culture (early Bronze) were unearthed last year at the Ust-Tartas site in Novosibirsk region.

Inside one of them researches found several dozen long beaks and skulls of large birds assembled into something looking like a collar, a head dress, or armour.

‘Nothing of this kind was ever found as part of Odinov culture in all of Western Siberia’ said researcher Lilia Kobeleva from Novosibirsk Institute of Archeology and Ethnography.

‘Why do we think this was a part of clothing? The beaks were assembled at the back of the skull, along the neck, as if it was a collar that protected the owner when he lived here.’

Read the rest of this article...

ARCHAEOLOGISTS TO SEEK GRAVE OF FIRST ROMAN EMPEROR TO DIE IN BATTLE, TRAJAN DECIUS IN 251 BATTLE OF ABRITUS, NEAR BULGARIA’S RAZGRAD

A collage showing a bust of Roman Emperor Trajan Decius, with the ruins of the fortress walls of ancient Abritus near Bulgaria’s Razgrad in the background.

Photo: Abritus Archaeological Preserve

An international archaeological expedition is seeking EU funding in order to search for the grave of Trajan Decius, the first Emperor of the Roman Empire to die in battle, namely, the 251 AD Battle of Abritus near today’s city of Razgrad in Northeast Bulgaria.

Both Roman Emperor Trajan Decius (r. 249-251 AD) and his co-emperor and son Herennius Etruscus (r. 251 AD) were killed in what was one of the greatest battles of the Late Antiquity when their forces tried to stop the barbarian invasion of the Goths near Abritus (today’s Razgrad), a major city and fortress in the Roman province of Moesia Inferior.

The precise site of the Battle of Abritus was identified only recently, in 2016, by Bulgarian archaeologists near today’s town of Dryanovets.

Read the rest of this article...

17 amphorae from the 3rd century BC discovered off Cannes

Credit: Marc Langleur

A campaign of underwater archaeological excavations has uncovered 17 amphorae dating from the 3rd century BC at a depth of twenty metres, not far from the Lérins islands off the Bay of Cannes.

According to Anne Joncheray, archaeologist and director of the Saint-Raphaël Museum of Archaeology, the 2,300-year-old amphorae are remarkably well-preserved and were likely used to transport locally produced wine to the Greek trading posts of the Mediterranean.

Read the rest of this article...

UN DÉPÔT DE MONNAIES EXCEPTIONNELLES DE LA FIN DU XVE SIÈCLE DÉCOUVERT À DIJON

Lors d’un diagnostic archéologique dans le centre de Dijon, près de l’ancienne abbaye Saint-Bénigne, une équipe de l’Inrap a mis au jour un dépôt d’une trentaine de monnaies d’or et d’argent de la seconde moitié du XVe siècle, originaires d'Italie et des états du Saint-Empire. Ce dépôt, d’un grand intérêt numismatique, a les allures d’un catalogue de portraits de tous les grands princes de la fin du Moyen Âge.

Read the rest of this article...

Sunday, June 02, 2019

Whipworm eggs found in 8000-year-old human coprolites. Andrew Masterson reports.

Archaeologists carefully excavating the neolithic village.

SCOTT HADDOW

Researchers picking though 8000-year-old human faeces have identified the earliest evidence of intestinal parasite infection in the mainland Near East.

A team led by archaeologist Piers Mitchell of Cambridge University in the UK travelled to the well preserve remains of a prehistoric village called Çatalhöyük, in southern Anatolia.

The site was occupied from about 7500 to 5700 BCE, and is today a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Apart from the extraordinarily good state of its survival, the village is of key interest because it was occupied around the period that populations in the region shifted from foraging to farming.

The change in both diet and lifestyle – particularly the emergence of permanent settlements – introduces the question of whether such a shift in living conditions also brought about a consequent change in disease profiles.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)